Lists

6 Movies, 1 Book

these make me wanna live

Sort by:

Recent Desc

More lists by yvaine the star 🌟

a special kind of magic

List includes: Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, Ella Enchanted

November 2022

0

@starseternals

to watch

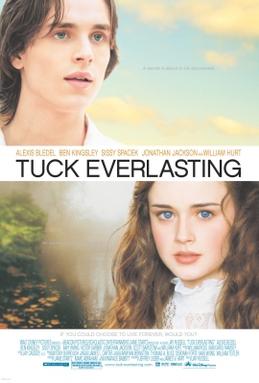

List includes: Because I Said So, Tuck Everlasting, Willow

October 2022

0

@starseternals

movies I really really like

cinematic masterpiece in my opinion

October 2022

0

@starseternals

tbr

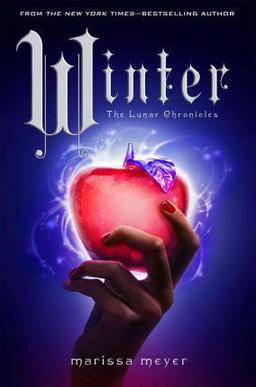

List includes: The Night Circus, Cloud Atlas, Winter

October 2022

0

@starseternals

girls night in

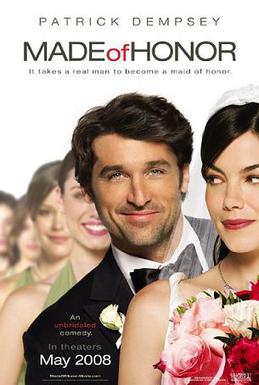

List includes: Made of Honor, 27 Dresses, The Proposal

August 2022

0

@starseternals

50% good

I really liked these until the second half of the movie completely ruined it

August 2022

0

@starseternals

Podcasts to listen to

List includes: Stuff You Should Know, Lore, Welcome to Night Vale

August 2022

0

@starseternals

porweful stories for powerful women

strong female characters and sisterhood bonds, and a bit witchy too

August 2022

0

@starseternals

cute guys in movies

List includes: Confessions of a Shopaholic, He's Just Not That Into You, When in Rome

August 2022

0

@starseternals