Lists

21 Movies, 2 Shows

Se med M +P

Sort by:

Recent Desc

More lists by Hallon hallonsson

utländsk

List includes: Three Steps Above Heaven, Love Likes Coincidences, I Want You

June 2024

0

H

@hallon-hallonsson

sett dålig

List includes: Self Reliance

February 2024

0

H

@hallon-hallonsson

Energy

List includes: Roswell, New Mexico, A Discovery of Witches

February 2023

0

H

@hallon-hallonsson

Seen TV

List includes: Glee, True Blood, Firefly

February 2023

0

H

@hallon-hallonsson

Action

List includes: The Dark Knight, Inglourious Basterds, Lara Croft: Tomb Raider

February 2023

0

H

@hallon-hallonsson

Starka bra

List includes: Slumdog Millionaire, Gladiator, The Matrix Reloaded

February 2023

0

H

@hallon-hallonsson

Sorgsna

List includes: Keith, A Walk to Remember, My Sister's Keeper

February 2023

0

H

@hallon-hallonsson

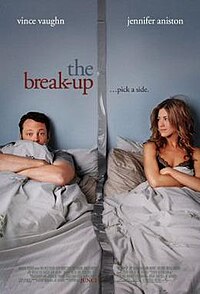

Filmer att se om och om

List includes: Becoming Jane, Penelope, The Break-Up

February 2023

0

H

@hallon-hallonsson

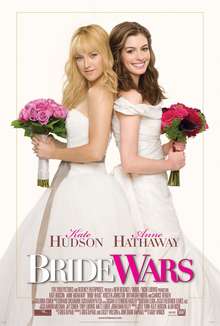

V+S

List includes: She's the Man, Bride Wars, How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days

February 2023

0

H

@hallon-hallonsson